It’s a remarkable thing, really. One of the most momentous events of your life involves handing over the keys to your entire self to a collection of strangers, most of whom you’ll never meet, whilst your memory of the whole thing will be lost to the effects of drugs that contain more words than is entirely healthy.

17 June 2025 – 0530

So, here we are. The start of the biggest day of my life. It’s not quite the wedding I once assumed it would be, but the somewhat less romantic (and far more medically complex) event of divorcing my pancreas. I’m surprisingly well-rested, which is a bonus, though I am getting a bit distracted by the view out of the window. That is, until I spot a sign for RFL Property Services with a logo that looks disturbingly like a set of coffins. Comforting.

0645

Arriving at a hospital this early is strange; it’s deathly quiet. Still, never to disappoint, the lifts provide their usual dose of light trauma on the way up.

0700

I arrive and book in to Ward 7, the day surgery ward (no… really) and get told that I’m to find bay 14; most helpful. After deciphering the appropriate signage, I find my spot in the room, which feels like arriving at the quartermasters, with your uniform laid out ready for you.

Still, at least I’m not in bay 15 as seemingly they need to give a urine sample and have a whole laminated sheet of instructions extra.

0745

Ah. The socks have arrived. You always forget just how sexy those things are, and, equally, how impossible they are to put on over the compression stockings. The stockings which, supposedly, are there to stop you from developing blood clots are definitely doing their job today, as they’re just cutting off the blood supply to my lower legs.

Swabs are also quickly taken to test for a variety of potential infections, ‘cos, infections are bad. We’ll just ignore the fact I washed myself in industrial-strength Chlorhexidine this morning.

0800

The parade of medical professionals begins! Well, more of a queue, actually.

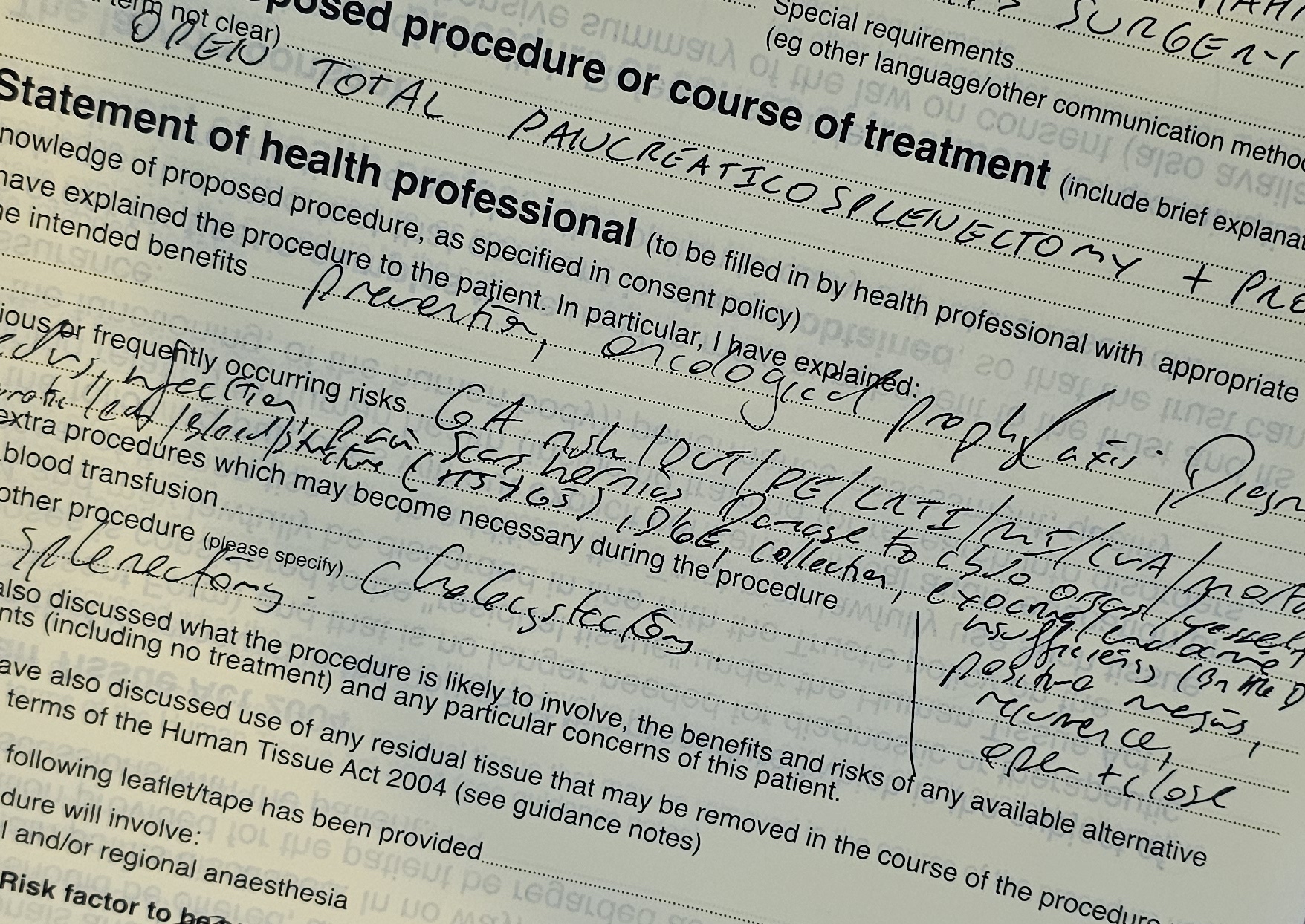

First up is one of the surgeons, armed with the usual comedy-oversized consent form. On this occasion, however, the form isn’t nearly big enough for the list of complications, which trails down the page. After the usual discussion about the small matter of potential death, I point out that since I’ve gone through the Herculean task of putting on the socks that we should probably get on with it.

The anaesthetist is next, looking reassuringly like a head gardener. As ever, he’s completely down-to-earth, making everything seem fine. I do wish they’d stop using the phrase “put you to sleep,” though. We did that to a pet dog once, and I’m fairly certain it’s a bad thing. He promises something to “make me relax” before I’m plumbed in, and then I’ll be sent off to sleep, remembering nothing but the first cannulation.

Several other surgeons pop in and out with various last pieces of advice and reminders, things like “when you wake up, you’ll have wires and tubes coming out from overwhere, so don’t panic”, my favourite though was the surgeon reminding me how to cough properly after the operation, mostly as I was too distracted by his Pokémon scrub cap to pay attention to what he was saying.

0815

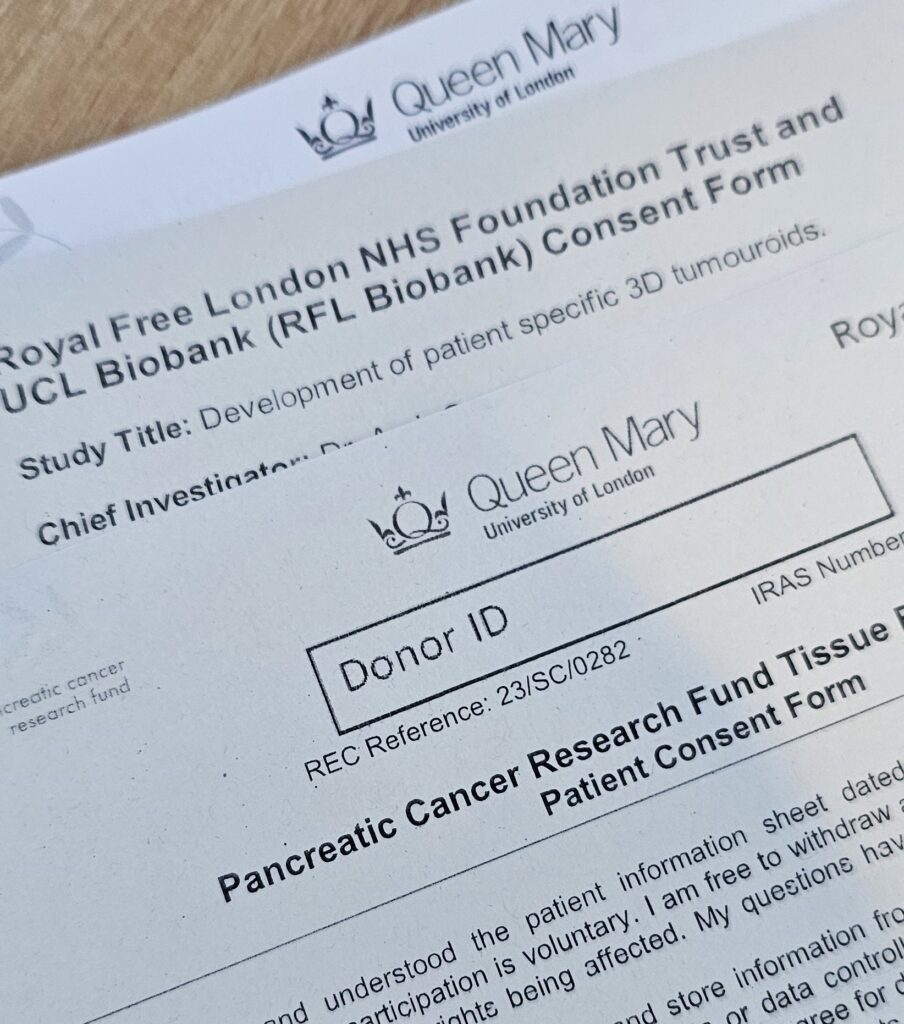

The final bits of admin are done, including a visit from a research scientist asking if I’d be happy to donate my resected organs. Of course, I agree. Some people refuse, which I find bizarre. I mean, they’re not going to be much use to me in a few hours, are they? If they can help someone do all the science, why on Earth not?

0830

And so my phone is finally taken from me, and I’m marched down to theatre with a few other patients. I note the mood in the lift is one of quiet contemplation, well, until I get tired of the silence and quip to my nurse, “you’d think we were going to a funeral or something,” which thankfully got her smile going.

I’m directed into the anaesthesia area of Theatre 7, where my anaesthetist is waiting. I’m asked to sit on the bed while they do the final checks that I am, indeed, me. Then, he manages to cannulate me without me even noticing. I ask him what the drug of the day is just as he’s administering it. I remember him starting to speak as a nurse clipped on the pulse oximeter, and then… nothing. The memory is just gone. Exactly as he promised.

And so, unbeknownst to me, an eleven and a half hour marathon was about to begin. During which time my actual survival was in the balance, dependant on the immense skill and brilliance of a huge team of surgeons, doctors and nurses but also, most humbling, the kindness of those strangers who have donated that most crucial of things: blood.